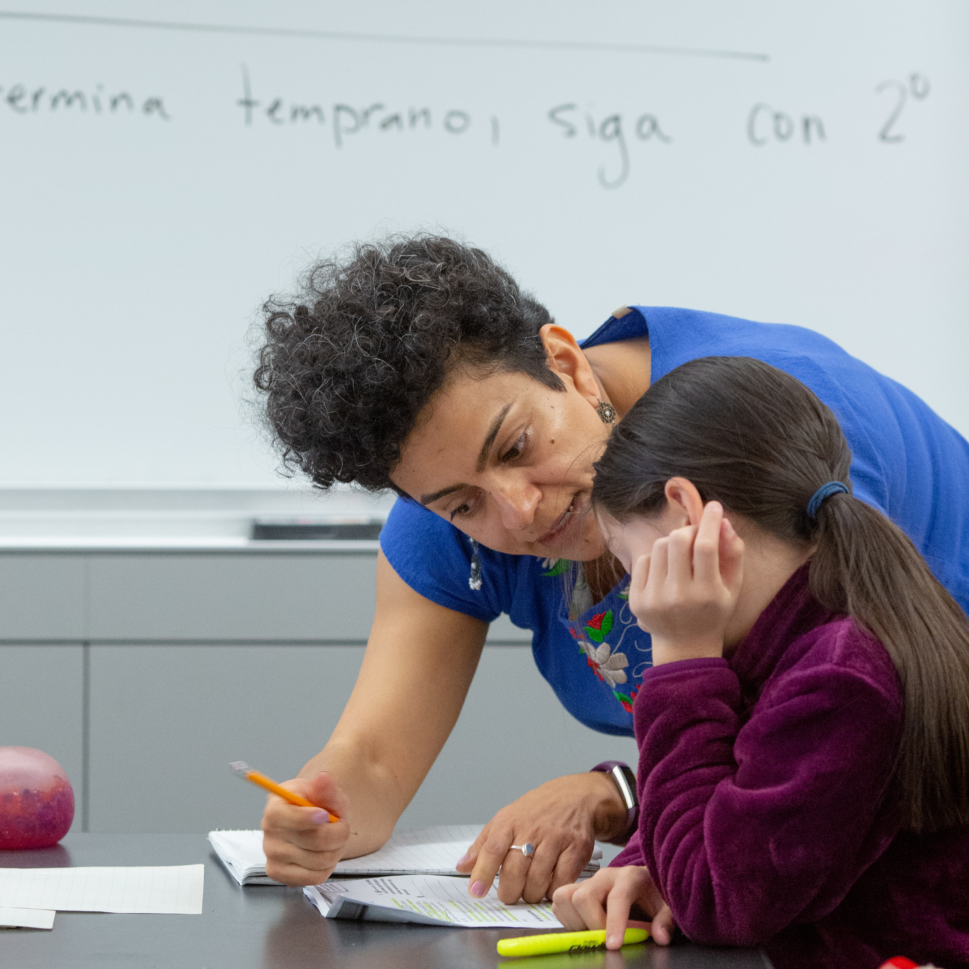

Photo by Allison Shelley for EDUimages

By Ryan Delaney

In the United States, the least experienced teachers are frequently concentrated in struggling schools, while research shows that teachers with 10-plus years of experience tend to be more effective at serving disadvantaged students than brand-new teachers. This juxtaposition has implications for improving outcomes for all students and closing achievement gaps.

When American teachers move schools during their career, it’s not toward the students who would benefit from their expertise. The usual path is from a challenging, lower-paying school early on to a more affluent school or district that pays better and typically has students with fewer academic or emotional needs.

These worrying trends have been called out by the Center for American Progress as well as the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ), which tracks teacher placement in U.S. states.

The good news is a just released NCTQ policy brief shows there are some promising strategies emerging in some states. Colorado, Kentucky, and Arkansas all do a good job tracking and reporting whether teachers are effective and how they’re being distributed, NCTQ says. A solid step toward giving all students the support they need to thrive.

But this is not just an American problem.

Photo by Allison Shelley for EDUimages

A recent report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development finds that in many countries effective teachers — those with experience and who spend a larger share of their time on actual instruction rather than classroom management — are not in the schools with students that need them most but rather often clustered in schools with higher-income students.

NCEE’s benchmarking work has identified some ways that effective teachers can be more equitably distributed among schools. Nathan Driskell, NCEE’s associate director of policy analysis, points out that “most importantly, the top performers prioritize developing high-quality teacher pools to ensure that every child is placed with an effective teacher.”

Ideally, teachers are given rigorous preparation and then when they are placed in schools, they are provided extensive support that leverages the expertise of more experienced, senior teachers. They’re given time to work collaboratively and to intervene with struggling students to help them stay on track.

When it comes to teacher assignment policies in particular, Japan, Singapore, and Shanghai offer good examples.

Japanese teachers are hired regionally and their school assignments change throughout their career, with moves happening as frequently as every three years early in their careers. Stronger teachers are assigned to the schools with students who need the most help. Japan also connects younger teachers with skilled colleagues so they can soak up their honed techniques.

In Singapore, officials place teaching applicants with an eye to where they’re needed most. Later, they may move from school to school or rotate through the ministry to get different kinds of teaching and administrative experiences.

Shanghai matches high and low-performing schools so teachers can move between the two buildings to swap ideas and practices.

Photo by Allison Shelley for EDUimages

Adopting these strategies in the U.S., where teachers’ preparation, hiring and development is decentralized, may seem impossible. Each district or charter school does its own recruiting and salary setting, meaning dozens of school systems competing for a pool of teachers in the same area. Poaching the good educators to a neighboring district by offering a little more pay is common.

Financial incentives to teachers willing to move to high-needs schools can help. However, solving the issue isn’t just about pay. Teachers regularly respond to surveys saying they want enough time to plan lessons and collaborate with colleagues.

“The U.S. might learn from what higher-performing systems have done to ensure that every school is a professional working environment where all teachers can collaborate, earn valuable work experiences, and grow,” Driskell says.

Getting experienced, talented, and diverse teachers in the classrooms of students who need them most will do a lot to heal the damage the pandemic caused in those communities.

For more information on this important issue, read NCEE’s Empowered Educators and Beyond PD reports, as well as our Blueprint.