By Brendan Williams-Kief

“Early childhood education and care today is not where it was even ten years ago,” said Dr. Sharon Lynn Kagan, lead researcher of the new landmark study The Early Advantage from NCEE’s Center on International Education and Benchmarking, in a webinar earlier this month, hosted by NCEE president Marc Tucker.

It is the response of systems around the world to this rapidly changing context and the concomitant evolution of the needs of young children that are the focus of The Early Advantage 1: Early Childhood Systems that Lead by Example, the first of two books produced by the study to be published by Teachers College Press.

Kagan, the Virginia and Leonard Marx Professor of Early Child Education and Family Policy at Columbia University’s Teachers College and Professor Adjunct at Yale University’s Child Study Center, and her team of internationally acclaimed researchers looked deeply into the historical and social contexts of systems in Australia, England, Finland, Hong Kong, the Republic of Korea and Singapore. The researchers examined how these varied contexts have shaped systemic approaches to early childhood policy, practice, and service delivery by these leading systems.

In the United States, according to Kagan, early childhood policy has been driven by the country’s historical legacy of independence, localism and entrepreneurialism. As a result, early childhood education and care in the United States is dominated by a lingering belief that the government’s role should be limited, often to only when families have “failed”, and decision making is often fractured between local, state and federal entities. This context stands in stark contrast to many of the systems of study in The Early Advantage. As Kagan explained in the webinar, broadly, three historical contextual frames have shaped the approaches of the systems of study.

First, the Nordic approach, exemplified by Finland, is characterized by heavy public funding and provision of services for early childhood education and care (ECEC), healthcare and child protection; a national framework with flexibility of implementation at the provider level; and limited, if any, formal national child or program monitoring.

Second, the Asian approach exemplified by Hong Kong, the Republic of Korea and Singapore is characterized by “moderate to heavy public funding” for ECEC within a mixed public-private provider environment. These systems tend to have national frameworks with structured pedagogy and substantial formal program monitoring, but limited formal child monitoring. Funding for healthcare and child protective services, according to Kagan, also tends to be substantial.

Third, the Anglo approach, embodied by England and Australia, features funding for early care and education services that can range from limited to heavy within a mixed, public-private provider environment. These systems typically have more robust, formal national child and program monitoring within a national early childhood framework featuring “moderately guided pedagogy”. These systems typically fund public health and child protection services at moderate to heavy levels.

But none of these systems, according to Kagan, are bound by those historical contexts and frames.

“These historic values really do influence the way countries carry out their early childhood policies, but …there are contemporary issues that all countries are facing that dramatically influence their approaches,” said Kagan.

For example, Kagan pointed to “pro natalist policies” of the Republic of Korea and Singapore designed to counteract falling birth rates and recent policies in Hong Kong, England and Australia aimed at reducing socioeconomic inequality. Similarly, the nature and amount of ECEC funding in Finland is not as generous as it once was as the country’s historic commitment to a robust welfare state comes in conflict with evolving economic realities. Further, pedagogy in ECEC is being rapidly shaped in both England and Finland by increasing immigration to both countries and the multicultural needs of these young children and their families.

Just as important as the “durable” historical and the more fluid present-day socio-cultural contexts are the range and depth of services for young children and their families, according to Kagan.

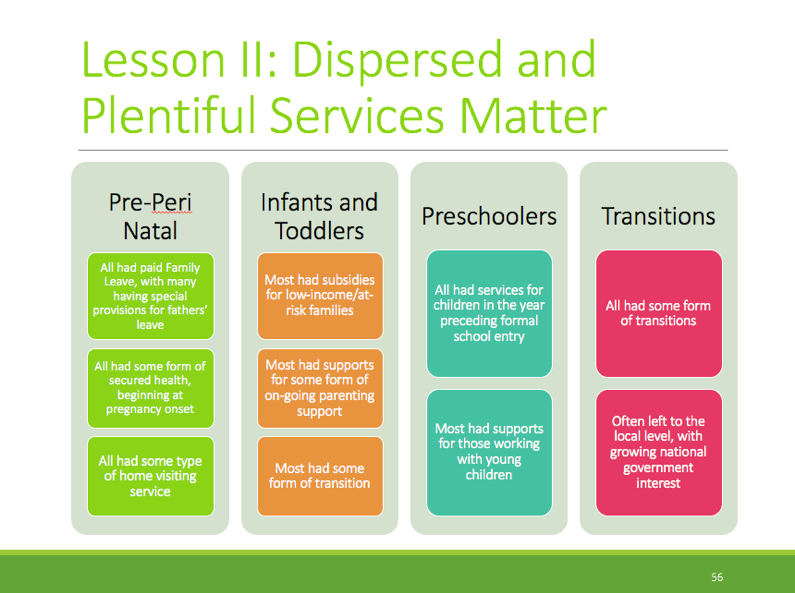

“If the first lesson is that context matters, the second lesson is that diverse and plentiful services matter,” said Kagan. “In each of these countries, there are an array of rich services that are available for children that we do not see [in the United States].”

The slide below from Kagan’s presentation outlines the broad and deep reach of services for young children and their families in these leading systems.

“These countries, scattered around the world, all do early childhood with very high quality, but they all do it very, very differently,” Kagan noted. “There is not one model, there is not one right approach. The approaches are very much modeled by the contexts.”

In the second half of her presentation, Kagan explored the evolving shape of each of the systems of study. For an overview of each country, see our Systems at a Glance. Kagan noted that despite the differences between and among the systems, each country can provide policymakers in the United States and beyond with important lessons about addressing the challenges and opportunities surrounding early childhood education and care.

For example, Australia, according to Kagan, shows that even in a decentralized political context similar to the United States, it is possible to build a national reform agenda and a national quality framework. England demonstrates how near-universal early childhood education can be achieved in a mixed, public-private provider environment that has strong monitoring and an emphasis on parent and community involvement in ECEC.

Kagan went on to explain how Finland’s commitment to supporting all students to achieve at high levels shows how these central cultural values can permeate the entire ECEC space while Hong Kong’s strong governance of a predominantly private sector provider environment shows how quality can be incentivized by public policy even within that context. The Republic of Korea shows how a country can overcome “inauspicious beginnings”, according to Kagan, to create one of the most robust and efficient ECEC systems in the world. Finally, Kagan noted that Singapore’s rapidly evolving, diverse provider landscape is characterized by a spirit of innovation and experimentation guided by a centralized Early Childhood Development Agency that has centralized its governance and is delivering some of the most innovative professional development for early childhood educators and at the same time seamlessly transitioning children to compulsory schooling.

While The Early Advantage 1 focuses on the “why” and “what” of early childhood education and care across these diverse systems, Kagan shared with the audience that the forthcoming second book, The Early Advantage 2, will focus on the “how” of ECEC. The Early Advantage 2, to be published by Teachers College Press in the Spring of 2019, will detail the essential pillars and “building blocks” that serve as the cornerstones of high-quality ECEC. These building blocks are the synthesis of the research team’s exploration of how the differing jurisdictions approach quality and access in their unique contexts.

Watch the full webinar below, and read more on the study, including “System at a Glance” overviews of each country of study, at www.NCEE.org/EarlyAdvantage.