On first thought, school building design may seem to have little to do with debates around improving teacher quality and elevating the status of teaching as a profession. Yet the design of a country’s schools can reveal a great deal about a nation’s educational priorities and vision for their students and teachers. Indeed, as schools in Shanghai, China and the United States show, the way a school is physically designed is a reflection of what roles teachers are expected to assume and the extent to which teachers are seen and treated as professionals.

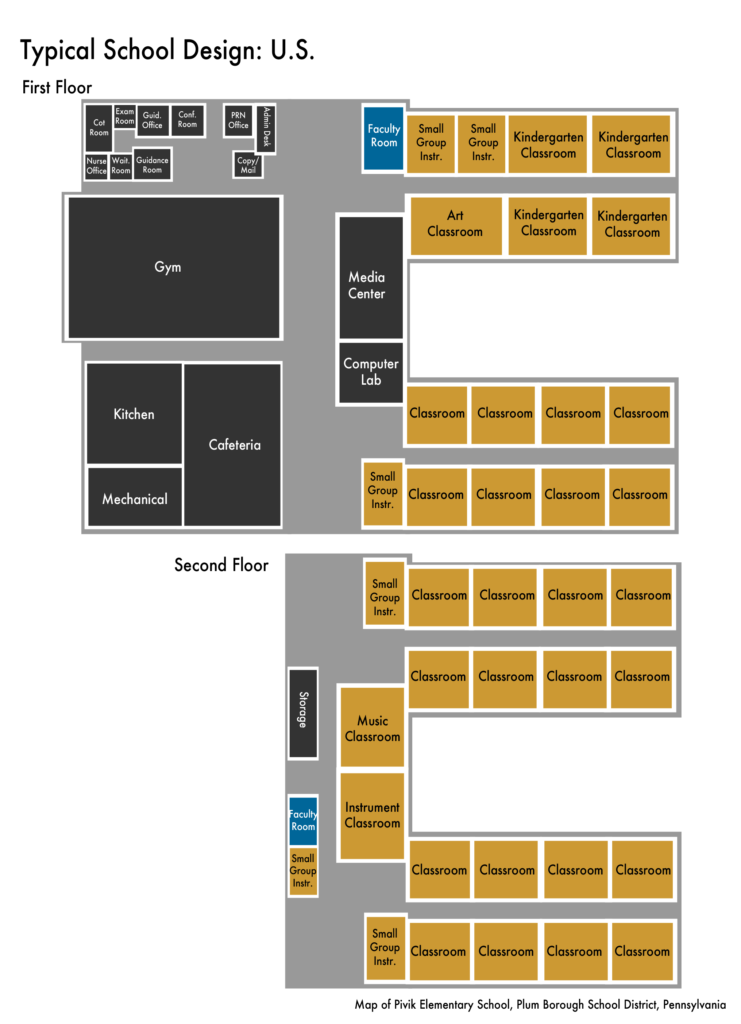

Consider, first, the United States. With few exceptions, school buildings in the U.S. share a similar design—hallways of classrooms, a cafeteria, a gym, a library, and some version of a teacher’s lounge. While the layout may differ from school to school, the general design is often the same. Indeed, what’s remarkable about American schools is just how unremarkable they are. And while technology and our understanding of pedagogy and effective instruction have changed over the last century, the design of most American schools has yet to catch up.

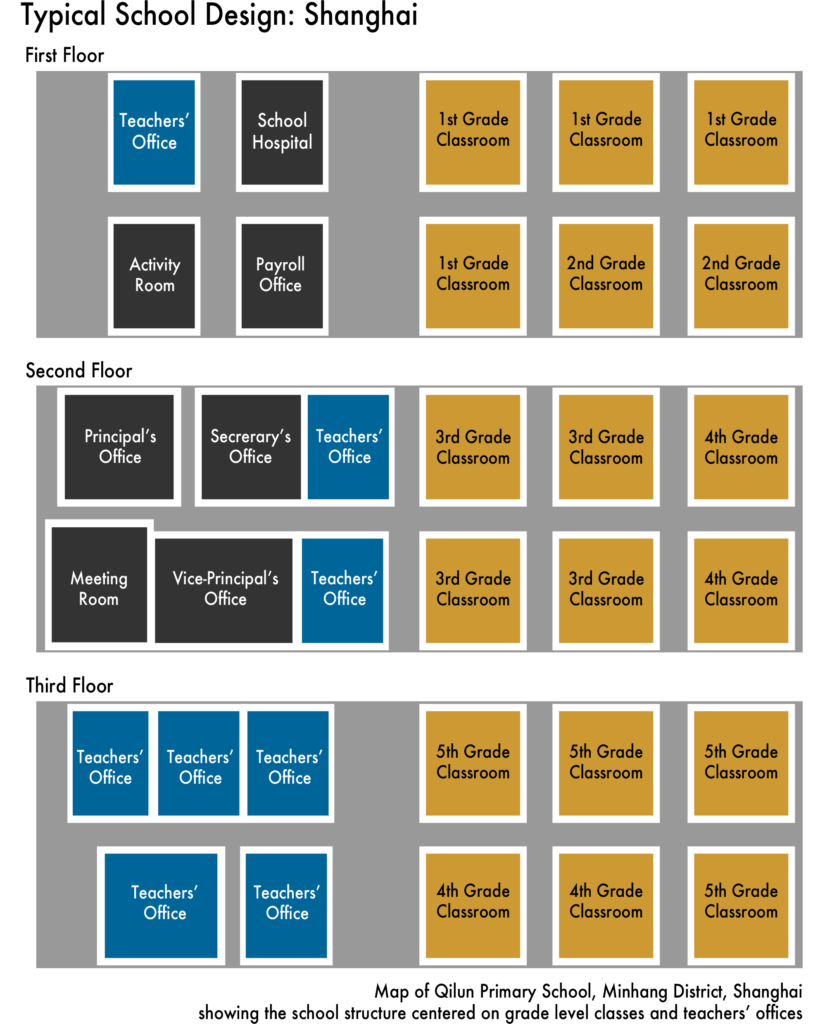

But in a typical school in Shanghai, China, the story is quite different. From the outside, schools in Shanghai may not appear much different than American schools. But open the doors and you’ll find a school designed in a way that promotes not just student learning, but envisions the school building as an environment where teachers are seen and treated as professionals. Many of the rooms in Shanghai’s schools are teachers’ offices or workspaces. That’s because, in Shanghai, there is a significant emphasis on teacher collaboration and professional learning. Teachers observe one another’s lessons, give each other feedback on instruction, and collaborate on lesson plans.

Supporting and collaborating with other teachers is not just something that teachers in Shanghai do out of convenience or courtesy. Rather, it is expected of all teachers. In fact, the average teacher in Shanghai teaches just 10-12 hours per week, spending much of the rest of their time planning and collaborating with their colleagues. Compare this to the 27 hours of teaching per week that U.S. teachers average and it becomes clear that the building is indeed a physical reflection of the expected work of the teachers in it.

This contrast in school design between the U.S. and Shanghai is telling. Not only is it indicative of the vast differences in the way teachers spend their time, it reveals the roles they are expected to assume.

In Shanghai, teachers collaborate with colleagues to refine and improve their craft and operate within a well-defined career ladder that provides financial motivation and a pathway for career advancement with roles of increasing responsibility linked directly to observing and mentoring new teachers, leading professional development, organizing research studies, managing school improvement projects, and more.

In the U.S., a teacher’s primary job is seen as delivering and facilitating instruction. Contrast this with places such as Shanghai where the teacher is not only an instructor but an important part of a collaborative team of professionals working to improve student learning across the school.

And we know that research suggests that when teachers are given more time for collaboration, there are positive effects on student outcomes. Of course, true reform of the teaching profession won’t come about by changes to the brick and mortar of a school but to the underlying policies that shape teachers’ roles in schools. But by examining the design of schools in top-performing countries, education leaders in the U.S. can learn a great deal about how those countries ensure that teachers are seen and treated as true professionals.

For more information on Shanghai’s schools, explore our profile of their education system or read our report, Developing Shanghai’s Teachers.