The Blueprint for Maryland’s Future: An Essential Investment, Now More than Ever

In my last blog, I reported on the extraordinary—and successful—effort made by the Maryland legislature to pass the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future bill in the few hours left in a session brought to an early close by COVID-19. The bill, as readers of this blog know, constitutes a thorough redesign of that state’s education system. It is intended to enable Maryland’s students to leave high school performing at levels comparable to the performance of high school graduates in the countries with the best and most equitable education systems in the world.

I ended that last blog reporting that the bill had been sent to the Governor. But, in the middle of April, the Comptroller forecast a 15 percent drop in annual state tax collections due to the economic effects of COVID-19 and the Governor froze state spending. There is still good reason to believe that the legislation will be implemented, but the timeline for the implementation may have to be stretched out over a longer period than first anticipated.

There will be those who will argue that the large increase in education funding required to implement the Maryland Blueprint is simply not affordable in a time of fiscal crisis. But it will not be possible to recover fully if there is a large and growing number of adults who require increasing amounts of state support because they do not have the education and skills needed to contribute in the kind of complex, high-tech economy that lies ahead once the recession is behind us. And, given that so many students have lost ground because of COVID-19, the powerful program to be provided by the Blueprint will be even more important for the thousands of students who begin school in the fall next year months behind a start line that is itself well behind where the start line should be. The Blueprint for Maryland’s Future is not an unaffordable cost; it is an essential investment.

In this blog and several to follow, I aim to give you a feeling for the design of the new system as it is laid out in the legislation. You can read the bill here. But that is no easy undertaking. It is over 200 pages long, and, like most legislation, the requirements are spelled out, but the rationale behind them is not. My purpose here is not to give you a blow by blow account, but to highlight some key features, note how they differ from standard practice, explain why they are important and show how they fit together into a new state education system unlike any in the United States.

That’s what lies ahead. In this blog, I explain how the Kirwan Commission went about its work and how our team helped the Commission get to the point at which it was ready to think not about introducing some reforms to the systems, but, instead, redesigning it.

System redesign is certainly not where most Commissioners started out. Most, notwithstanding the formal charge that included researching the top-performing education systems in the United States and abroad, assumed that the real task was the other charge: revising the Maryland school funding formulas. They came prepared to engage in the usual political jousting that produces winners and losers in any effort to revise school funding formulas. They were to be forgiven for thinking that the requirement to look at top-performing education systems was not going to be all that important, because they had been told for years that Maryland had one of the best education systems in the United States. And the United States was the one remaining superpower. Surely Maryland’s education system was already one of the best in the world.

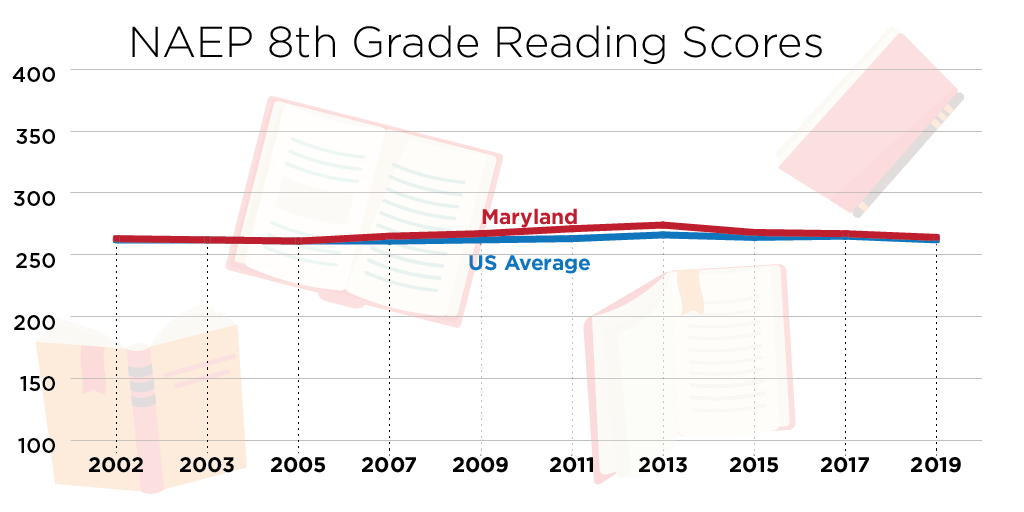

Our first job was to help the Commission members understand how Maryland’s students really stacked up as well as how all the major components of the education system performed and how efficient the system was. The state believed that it had one of the best if not the best education system in the United States because Education Week had put the state at the top of its state league tables for several years running in its annual survey of states’ education performance. But it turned out that the performance of a state’s students on the National Assessment of Educational Performance (NAEP) was only one of many measures that Education Week takes into account to determine its state education rankings. The Commission was shocked to discover that Maryland students’ NAEP performance in reading, mathematics and science was right in the middle of the distribution for the whole United States. Then we showed them rankings of the states on wealth and education levels. Maryland is one of the wealthiest states in the nation and one of the best educated in terms of attainment. And Maryland also has one of the most expensive state education systems. By any combination of those measures, it should have been performing far better than it was.

After that data sank in, we showed them the statistics for national performance on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), the triennial international comparative assessment of 15-year-olds in reading, mathematics and science. U.S. students, they saw, did reasonably well in reading and much less well in science. Thirty countries outperformed the U.S. in mathematics, many of them developing countries. So, far from being a state with the best education system in a country with one of the best education systems in the world, Maryland had a mediocre education system in a country with a mediocre education system, despite being in a wealthy state with a highly educated population. That was very sobering for the Commission members.

But not decisive. After all, if Maryland could run a successful economy with the graduates of such a system, what’s the problem? Maybe the schools, though not doing well in comparison to those of other states and nations, were doing well enough. Maybe all the state needed to do was to bring its funding formulas up to date.

So, we shared with the Commission the results of a national study that included Maryland that we had done on what it really means to be college and career ready. It showed, in effect, that it was highly likely that half or more of the graduates of Maryland high schools had only a very weak grasp of middle school mathematics, were unable to comprehend texts written at a 12th grade level and were very poor writers. Then we showed them comparable data for the typical graduates in countries in which reading and mathematics achievement was much higher, the students had a better command of science and, the clincher, the same students, when they joined their nation’s workforce, charged much less for their labor than our workers. And finally, we shared the data on the rate at which robots and intelligent machines were taking over the kinds of routine work done by workers with only the skills that most Maryland graduates left school with.

At that point, it was clear to the Commission that the state was on a collision course with reality. A large fraction—half or more—of Maryland students were being poorly educated for jobs that would probably cease to exist in the near future while other countries were educating the vast majority of their students for the jobs that would exist and doing so for a lower cost per student than Maryland was spending.

What the Commission’s Chair, Brit Kirwan, wanted to know was…how are these other countries able to do a much better job of educating their students and do so at a lower cost?

To answer that question, we shifted gears. The Commission asked us to compare the education policies and practices of the top-performing countries and states with Maryland’s policies and practices. We picked four countries from among the top 10 performers on PISA and three of the top states on the NAEP league tables for this comparison.

Over the years, NCEE had identified, from our comparative analysis, what we call the 9 Building Blocks for a World-Class Education System. These are the common elements of all of the top systems whose students perform at high levels, with equity and efficiency. They are: 1) Provide strong supports for children and their families before students arrive at school, 2) Provide more resources to those students that need more help, 3) Develop world-class, highly coherent instructional systems, 4) Build a qualification system with multiple no-dead-end pathways for students to achieve those qualifications, 5) Assure an abundant supply of highly qualified teachers, 6) Redesign schools to be places in which teachers are treated as professionals and have incentives and support to continuously improve their professional practice and the performance of their students, 7) Create a modern, effective system of career and technical education and training, 8) Create a leadership development system that develops leaders at all levels to manage such systems effectively, and 9) Institute a governance system that has the authority and legitimacy to develop coherent, powerful policies and is capable of implementing them at scale.

Over many meetings, the Commission came to see this is not a list of nice-to-haves from which one can select a few that are easiest to do and leave the rest for another day. They saw that, together, these nine building blocks are all parts of one coherent system. Each building block can be built in different ways in different places. They can be implemented with different strategies at different points along a timeline. But all of them are necessary and a good plan must keep all of them in mind from the beginning.

But all of this is very abstract. What carried the day was the data from the gap analyses that, again, compared Maryland’s system with three top-performing education states and four top- performing education nations. We worked with Brit Kirwan and the Commission’s legislative staff lead, Rachel Hise, to develop a schedule for the Commission meetings that would enable us, for each of those meetings, to concentrate on one or a few of the building blocks. We would come to each meeting with detailed data comparing the policies and practices of the selected four countries and three states for the building blocks to be discussed. NCEE also brought to each of these meetings our own recommendations as to what Maryland should do by way of making policy for that building block. It was, I believe, these meetings that fully engaged the Commission in the work and gave them a coherent, concrete and powerful vision of what Maryland could do and needed to do to build and implement a world-class education system for all students in the state.

To access the full gap analyses NCEE did for Maryland, go here. To give you a feel for what the gap analysis showed, here is an excerpt focused on the first building block, Strong Supports for Children and Their Families Before Students Arrive at School:

“Most of the top-performing countries provide government support for families with young children that, in breadth and depth, far exceeds the support provided by any state in the United States. This often includes a family allowance, paid family leave for the mother or father (often for a year of more), free medical care services, wellness care and parent education. Singapore, for example, provides a one-time ‘baby bonus’ equivalent to $5,737 for each of the first two children and $7,172 for each additional child. They also open a Child Development Account that can be used to fund child care and many other educational services and put $2,141 in the account at birth [with more in each of the subsequent years]. These service packages are typically designed to enable one or both parents to stay at home and bond with their newborns for their first few months to two years or more, with no sacrifice in income. After that, these countries provide highly subsidized, high-quality child care on a schedule that enables the parents to work a full day without worrying about the welfare of their children….All of the countries benchmarked as top performers offer free or very low-cost, high-quality early childhood education for all three- to five-year-olds….responsibility for the availability and quality of child care services is lodged in the Ministries of Education, so that the provision of these services can be coordinated with the early childhood education system and the system for formal schooling, so there is a smooth progression in the design and operation of these services as the child develops.”

The gap analysis goes on to point out that there is no comparable suite of services anywhere in the United States.

The full gap analysis provides a detailed rendering of the services provided by each of the benchmarked countries and states. The cumulative effect was very powerful. The Commission had earlier learned that the per-pupil cost of formal school in the United States is 150 percent of what it is in many of the top-performing countries. But, when they reviewed the detailed data, the Commission realized that some or all of the higher cost of schooling in the United States is due to gross under expenditure on families with young children before those children first appear at the schoolhouse door. They would have to look at the support system for families with young children along with support for children while in school as all parts of the same system. After a very vigorous discussion, the Commission decided to expand the scope of the recommendations to include family services, childcare services and early childhood education with the scope of its mandate and as fit subjects for its recommendations.

Overall, I think it is fair to say, the gap analyses had a profound effect on the Commission, serving to sweep away misconceptions and present possible courses of action that were obviously well conceived and effective policies without any precedent in the United States. These analyses were constantly raising the sights of the Commission and expanding the range of the possible solutions to problems long thought impossible to solve. Our recommendations for each of the building blocks would have seemed outlandish without these compelling pictures of what the top performers were doing and why they were doing it.

As the meetings organized around the gap analyses proceeded, our little informal steering committee— Brit Kirwan, Rachel Hise, my colleague, Betsy Brown Ruzzi and I—roughed out the plan for the rest of the work of the Commission. The Commission as a whole, having considered the research and discussed our recommendations, would meet as a committee of the whole to arrive at a preliminary consensus on policy recommendations. Then the Commission would break into four groups, each one to work with the Maryland Department of Legislative Services, NCEE and the Commission’s finance consultants, APA, to figure out what it would cost to implement those policies in Maryland over a period of 10 or so years. Then the Commission would reconvene as a committee of the whole to consider the recommendations of each group, reconcile differences and come to a consensus on final recommendations. In the event, when all of that was done, the report of the Commission was transmitted to the Governor and the legislature. One more task, figuring how much of the recommended budget should be financed by the state and how much by the counties, was left to a small group that reported to the legislature before the legislature took up the proposed legislation.

In my next blog, I will take up one of the large substantive issues considered by the Commission and explain how they dealt with it. This whole series of blogs is intended to help the reader understand how other states might go about comparing their performance to that of the world’s top performers and then redesign their systems for comparable performance.

We are proud of the role we played, but we are under no illusion that we made the decisive contribution to the work of the Commission. That contribution was made by the Commission itself. That is not false modesty on our part. It is plain fact. It is one thing to analyze and recommend, quite another for a group composed of legislators, people who head organizations representing stakeholders and others with a lot on the line to come to agreement on what amounts to a radical plan to change a system so central to the lives of so many. Brit Kirwan and Rachel Hise earned the trust of the Commission members on the strength of their competence and obvious integrity. Their leadership made all the difference.